Cold Fronts, JPCZ, and Other Excuses

The latitude of my last landing is similar to Lisbon, in Portugal. That’s about a third of the way down the coast of Honshu. I’m trying to go south, but currently going nowhere.

Since the beginning of the winter, winds have been blowing from the NW on to the Japan Sea coast. 9 out of 10 days are windy, with rough seas and a dangerous lee shore. The cloud base rarely lifts, and most days bring rain or snow.

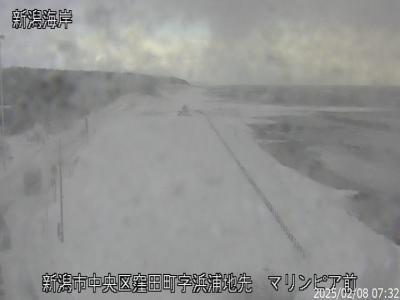

From a safe distance (somewhere near Tokyo) I spent much of yesterday consulting the webcams. On the west coast, snow is back down to sea level in what is reported as the strongest cold front for years. Currently, you have to go about 300 miles further south to find coastline that is not painted white.

[Text continues beneath the webcam images]

The term “cold front” being used to explain these conditions confused me, so I read about what is going on, and got carried away with my research. I’m no meteorologist, but I think this is mostly right– happy to be corrected if not.

Cold Fronts (North Atlantic Version)

Cold fronts as I understood them (UK perspective) are an abrupt boundary where cold air bulldozes away (displaces upwards) warmer air in its path. Weather at the front may be severe: with rain, snow and perhaps thunderstorms. But the abruptness of the boundary means that, for a (relatively) static observer, cold fronts pass through quickly. The cold front “announces the arrival” of a cold sector that has cooler and drier air.

Cold Fronts (Japan Winter Version)

The situation in Japan is much more static. A simplified explanation goes something like this. In winter, East Asia and Siberia in particular are intensely cold, and high pressure dominates. Pressure over the Pacific Ocean is lower. This pressure gradient is responsible for the run of NW winds coming across the Japan Sea.

The Japan Sea is warm. It does a good job of staying warm as it is being continually renewed by Pacific Ocean water coming in from the south and spilling out at the north. I feel this current. When sailing, it significantly hinders progress.

At sea level, the cold air from Siberia takes in heat and moisture as it flows across the warm sea towards Japan. The upper level air does not receive this warming. This is an unstable situation. The warm air pushes up into the cold, eventually condensing into clouds, snow and rain. By the time this air has reached Japan it is delivering the weather as described above and depicted by the webcam images. It’s good for skiing (especially up high, where the uplift caused by the terrain causes greater snowfall) but lousy for windsurfing.

With particular significance for the island of Honshu (at mid latitudes), the Siberian air that it will receive must detour around a North Korean mountain range before it reaches the sea. The incoming air rushes around the mountains on either side, and downwind of them (over the sea) there is a convergence zone. Where these airflows converge, they force stronger uplift of warm, moisture-laden air from sea level, intensifying snowfall.

The convergence zone, known as the Japan Sea Polar Air Mass Convergence Zone (JPCZ), has effects that are felt far downstream, and Honshu is in the firing line to receive them. The JPCZ is often likened to a snow cannon.

During Japan’s winter, cold air is (usually) already dominant, but there is variation in the degree of coldness of the flow from Siberia. Sometimes a deep “cold air outbreak” occurs. When this happens, if a sufficiently distinct boundary exists, it may be classified as a “cold front”, and more intense weather is likely on the way.

Key Differences

Use of the term “cold front” is quite distinct in each scenario. In the North Atlantic low context, the action happens at the boundary between cold and warm sectors. For an observer at a given location, the front passes quickly.

In the Japanese winter context, there is no warmer sector to displace. Instead, all the action happens within an existing cold sector, and the snow can go on piling up for days or even weeks.